Tabletop Role-Playing Games and Mike Pondsmith’s Road to Cyberpunk 2077 (2020)

My talk here is about Cyberpunk 2020, and is part of a larger project of game genealogy, in the hope that we might be able to further situate digital games in terms of their analog predecessors and contemporaries.

To those of us interested in genre analysis –– acknowledging that all genres are always hybrids –– I want to remind us all that the cyberpunk sub-genre’s predecessors and contemporaries emerge from unexpected sources beyond simply William Gibson and other literary figures. Finally, biography, identity, and ideology should not be excluded in our discussion of game mechanics and cyberpunk culture. It is with these premises that I’ll now proceed to discuss one of the most influential figures in modern cyberpunk media, Michael Alyn “Maximum Mike” Pondsmith.

Our year of 2020 is of crucial importance in cyberpunk media, for it is when Pondsmith’s famous tabletop role-playing game (TRPG), Cyberpunk 2020 (1990) is set. TRPGs involve shared narration of an unfolding story among several players, who roll dice according to rules governed by game books and a game referee to determine uncertain outcomes. In this “dark future” first imagined over 30 years ago, players take on the role of characters, so-called “edgerunners” who are “survivors in a tough, grim world, faced with life and death choices. … [They] are the heroes of a bad situation, working to make it better (or at least survivable) whenever they can. … [The] quintessential Cyberpunk character is a rebel with a cause.” (Pondsmith, et al. 3)

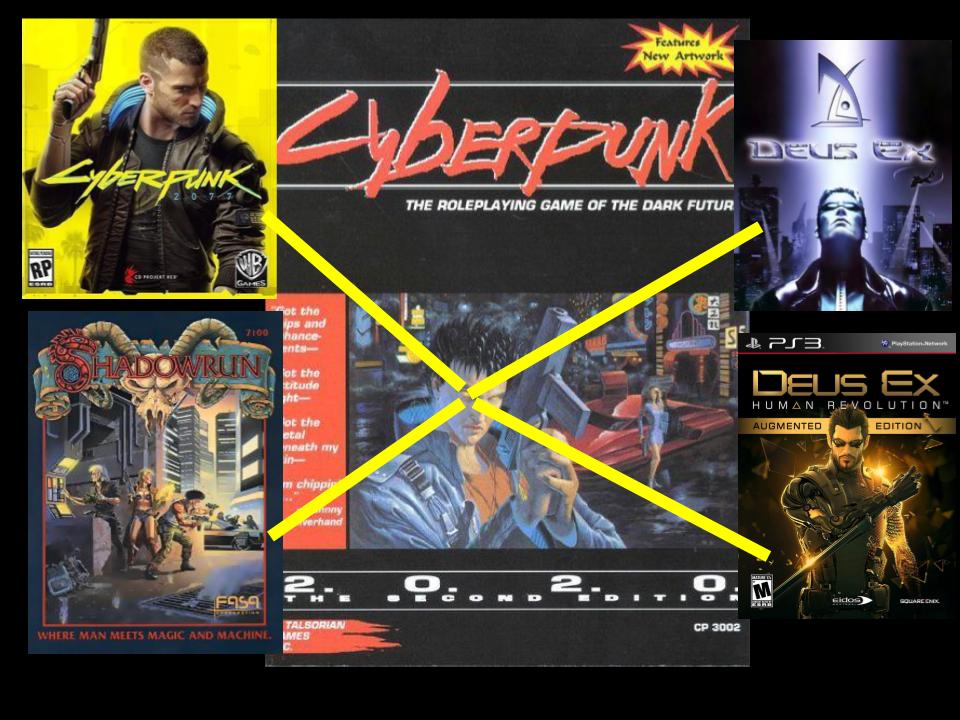

Our arrival in this canonical cyberpunk year has also been accompanied with the ever-delayed release of the hotly anticipated Cyberpunk 2077 (2020) videogame, designed by Polish game studio CD Projekt Red, which is known worldwide for the Witcher series. Unlike many videogames licensed from tabletop RPGs, Pondsmith has been intimately involved with this game’s creation from its announcement in 2012. This has thrust Pondsmith into the worldwide gaming spotlight a second time. The first time was when the original Cyberpunk (1988) and Cyberpunk 2020 (1990) were worldwide hits, immediately optioned for films and videogames already in the early 1990s. Cyberpunk and copycat lines such as FASA’s Shadowrun (1989) or Steve Jackson Games’ GURPS Cyberpunk (1990) quickly drowned out spacefaring sci-fi TRPGs as subjects of interest. Pondsmith’s company R. Talsorian Games became a celebrated 1990s success story, delivering him both an Origins award and the presidency of the Game Manufacturer’s Association (GAMA). Cyberpunk 2077 signals the triumphant return of R. Talsorian’s meticulously assembled dark future world to be enjoyed by millions of digital gamers during a time when video games have enjoyed more visibility than ever.

It is not an overstatement to say that Cyberpunk 2020 mechanically and aesthetically framed not only its direct game adaptation, but almost all subsequent game adaptations of the cyberpunk subgenre, including the Shadowrun and Deus Ex franchises. Lesser known, however, is the highly specific genealogy of Cyberpunk 2020 outside of its obvious filmic and literary foundations. Pondsmith has given much credit for his original game-mechanical ideas to Marc Miller and his space-faring hard sci-fi TRPG Traveller (1977), with the Cyberpunk Interlock™ system owing much to iterations of Pondsmith’s early anime mecha fighting TRPG Mekton (1984). Just as cyberpunk emerged from a faction in New Wave sci-fi, so too did the breadth of cyberpunk game patterns emerge from a curious confluence of space exploration and mecha combat, coupled with Pondsmith’s own background as a Black American steeped in child psychology, the US military, and the American West Coast tech sector. So here I’m arguing that Cyberpunk 2020 comes from a marriage between hard sci-fi and anime fandom –– not Dungeons and Dragons (1974) –– and that Pondsmith’s biography continues to ripple through some of the major components of the game: a meticulous focus on weapons, an open-ness to cultural diversity and intermixing, the importance of lifepaths, and a conscious revision of the way the Internet operates as our own present-day tech has evolved. In other words, it’s not so easy to separate this influential game from its creator.

A brief summary of Pondsmith’s biography is helpful. He was born to a military family –– his dad a US Air Force officer, his mom a psychologist –– and moved around the world until he settled in Berkeley, California. He describes the outfit of his younger years as “mirrorshades, a ratty army jacket, motorcycle boots and carried a six-inch knife” (Purchese 2017). He received degrees in graphic design and behavioral psychology from UC Davis, aspired to become a child psychologist, but wound up instead working for a packaging company California Pacific, which manufactured boxes for the then-unknown Ultima (1980) series of games by Richard Garriott. His work in typesetting combined with his interest in game design when he made a hack of Marc Miller’s sci-fi game Traveller called Imperial Star in 1982. What followed was his take on Mobile Suit Gundam (1979-1980) called Mekton, the founding of R. Talsorian as the first Black-owned TRPG company with $500 from his mother, then a comedy game Teenagers from Outer Space (1987) before landing a hit with Cyberpunk, which struck a nerve among fans of William Gibson, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), and Bruce Sterling’s Mirrorshades (1986) anthology. Tensions with the fans over increasing Japanese anime influences on Cyberpunk in the mid-1990s meant that the studio would develop alternative product lines such as Dream Park (1992), the youth rebellion game CyberGeneration (1993), the breakthrough steampunk TRPG Castle Falkenstein (1994) and cyberpunk anime classic Bubblegum Crisis (1996). By the late 1990s, however, the bottom had fallen out of the TRPG industry, and Pondsmith put his company on ice and worked for Microsoft in Washington, where he developed video games for the early XBox console in the early 2000s. He then put out a new edition of Cyberpunk in 2005 that was panned by fans and critics alike, gave up a second time, taught game design at DigiPen in Redmond, Washington, and then Kickstarted Mekton Zero in the early 2010s before Cyberpunk 2077 became a widespread sensation and led to media attention, which highlighted Pondsmith as an innovative world builder and games guru.

It is curious that most of us who grew up with R. Talsorian’s attractive game lines didn’t know Pondsmith was Black. Game publishers were admittedly fairly anonymous unless one regularly attended conventions, and Pondsmith’s social background was simply not mentioned in early press coverage of R. Talsorian’s releases. Does, then, the highly influential Cyberpunk TRPG franchise fall under Afrofuturism, as outlined by Isiah Lavender III and Graham J. Murphy (2020) in the Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture? Their vision of Afrofuturism involves peoples of African descent portrayed as inheriting and creating technological progress and social liberation, with examples such as Samuel R. Delaney (Stars in My Pockets Like Grains of Sand, 1984), Nnedi Okorafor (The Book of Phoenix, 2015), and Walter Mosley (Futureland, 2001). Cyberpunk as a white science-fiction genre has us default to considering Cyberpunk TRPGs to be white, too, and Pondsmith’s team at R. Talsorian is admittedly very much so. But for its time, the R. Talsorian team also indulged in a few flourishes of Black American culture. For example, the Cyberpunk 2020 word for close friend or family member, “chombatta” is described as “Neo-Afro American slang for friend, family member (Pondsmith, et al. 34).

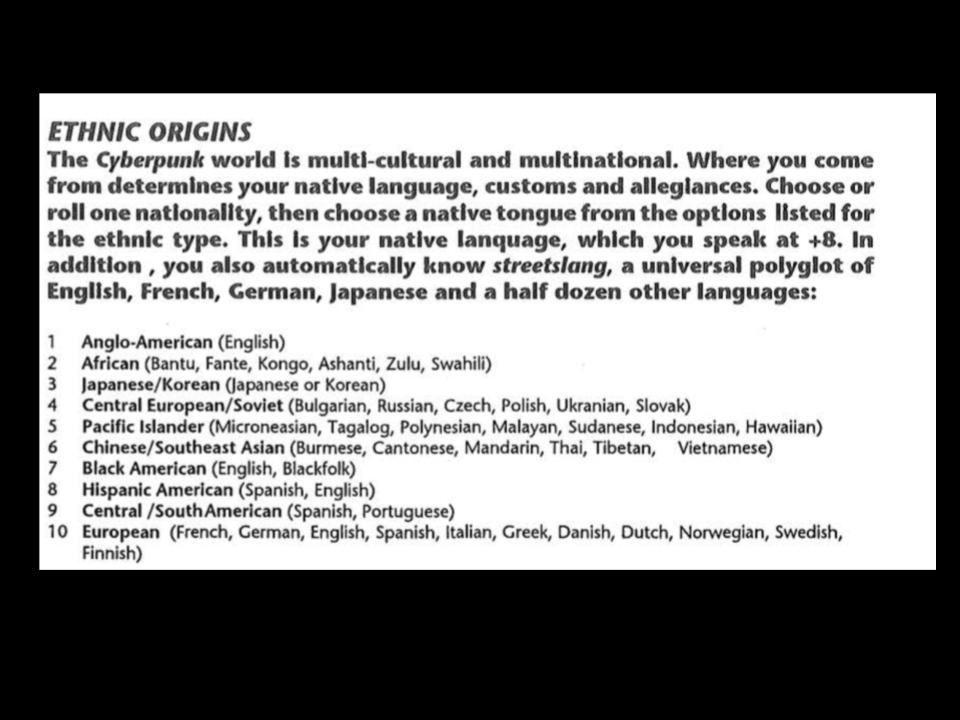

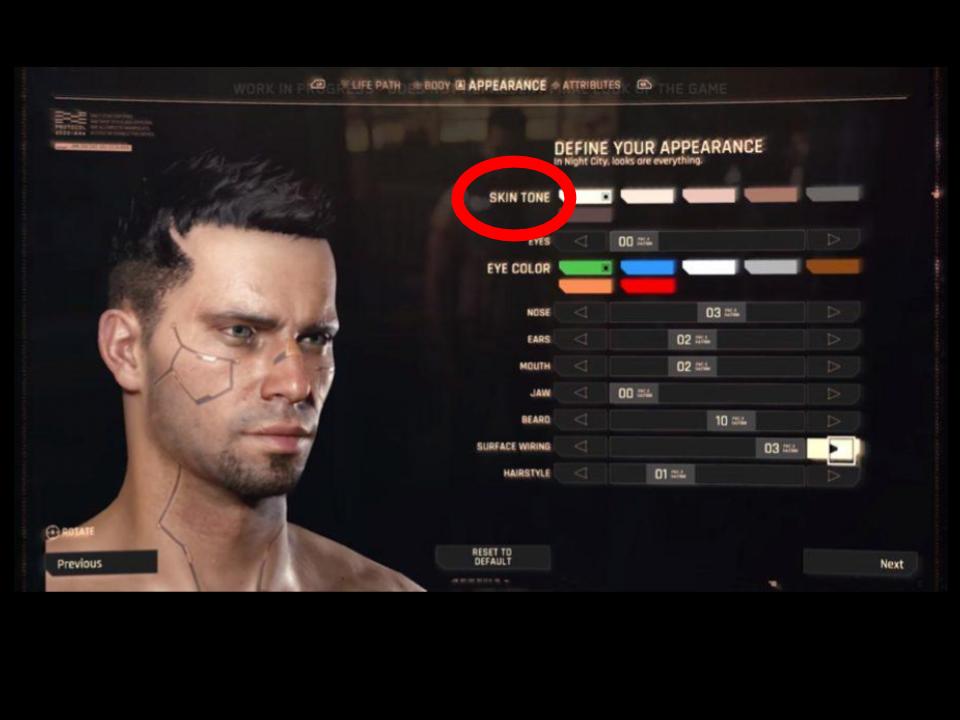

Each character also has an “Ethnic Origin” as “the Cyberpunk world is multi-cultural and multinational. Where you come from determines your native language, customs and allegiances.” (ibid.) The 10 possible ethnicities subdivide Anglo-American from European from Central Europan/Soviet, and makes conscious distinctions between African and Black American origins, between Pacific Islander, Japanese/Korean, and Chinese/Southeast Asian origins. Cyberpunk 3.0 (2005) features Pondsmith’s mugshot, as well as predominantly non-white action figure images, to convey that its dystopian vision is at least not of a white-dominated future. As the first-ever Black-owned TRPG company, R. Talsorian is both attentive to matters of race and ethnicity without being overtly preoccupied with them. Cyberpunk 2077 reduces race/ethnicity to “skin tone,” which is perhaps a AAA compromise from that position.

In fact, both Pondsmith’s work and Cyberpunk 2077 have been subjected to withering critiques of their social forms of representation. Attebery and Pearson (2018) note that Cyberpunk 2020 served as the origin point of the “psychic ‘budget’ to limit cybernetic augmentation as a game mechanical balance on player power.” (72) Effectively, the more cyberware you add to your character in Cyberpunk 2020, the more the character loses their “Empathy” stat and becomes increasingly anti-social. This both offers a specific vision of what it means to be human –– and what one sacrifices in the dark future to remain fashionable and deadly –– as well as an ableist stereotype of those with prosthetic limbs or organs somehow being “less” human. The Cyberpunk 2020 unabashedly indulges in the rhetoric of “tribes” to describe rolling biker gangs, and one edition of Cyberpunk 2020 contains an offensive “Cultural Similarity Table,” which Kazumi Chin (2020) posted for an open-season Twitter bashing earlier this year as Aboriginal and Japanese cultures are branded as “alien” vs. Australian (distinct from Aboriginal!) and American, which are “similar” (27). Moreover, the representation of trans* individuals in the Cyberpunk 2077 video game, supposedly a space of limitless body modification, still boils trans* individuals down to their genitals and male/female voices, which will then invite constant misgendering from the entire cast of NPCs as one plays. But the conversation that I think is particularly pertinent to Pondsmith’s long-tail influence on the genre is the question of firearms; guns are what make the Cyberpunk TRPG tick.

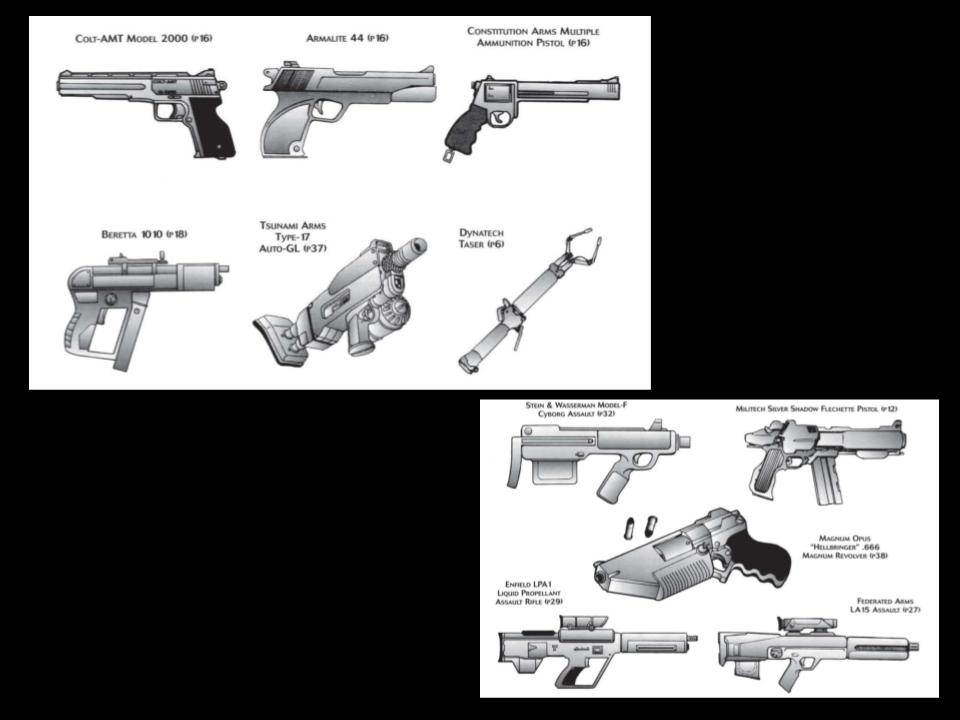

“Cyberpunk weapons are large, black, lethal, dangerous things that look distinctly unfriendly.” Mike Pondsmith noted in a recent interview about how he desk-rejected earlier cartoon-ish raygun designs by CD Projekt Red “… They look like ‘I’m here to kill you now.’” (“Cyberpunk creator…”) He emphasizes later that a “core element” of the Cyberpunk universe is that the weapons are “realistic,” nodding with approval at a wall of real guns used for modeling at CD Projekt Red. We can recall that Blade Runner (1982), Pondsmith’s primary visual inspiration for the TRPG, had exactly two types of gun. Cyberpunk 2020, by contrast, devotes 7 pages to different varieties of weaponry, with Derek Quintanar’s quintessential Cyberpunk weapons guide Blackhand’s Street Weapons 2020(1995) containing “over 250 weapons compiled in one volume *plus* one new gun.” Of course, Pondsmith may have been simply participating in a larger cultural moment in gun fetishization: R. Talsorian’s TRPG competitors TSR and Palladium Games devoted similar amounts of space to weapons tables and weapon-rack-style imagery. Nevertheless, Pondsmith’s military background and overall closeness with law enforcement officers (2020) is distinct from, say, William Gibson’s draft-dodging and Greg Egan’s outback pacifism. Guns are at the core of Cyberpunk 2077, I think, because they are fundamentally important to Pondsmith, his team, and the overall fandom, rooted in American exceptionalism and gun culture. West Coast gang violence of the 1980s mixes together with militaristic fantasy here.

Although I’m certain the audience of this talk is aware of this, cyberpunk as a sub-genre came much more from a core of science fiction authors interested in space and space travel than gritty urban fiction. This is also the case for Pondsmith, who took heavy inspiration not only from Blade Runner but in particular from Marc Miller’s space opera TRPG Traveller (1977). Pondsmith remarks that Traveller was “the first true science fiction RPG in a world of D&D wannabes and fantasy flavors-of-the-month” (Lowder 331). From a game mechanics perspective, Cyberpunk 2020 is built on the bones of Traveller, not Dungeons & Dragons. As in Cyberpunk, players in Traveller do not start with a novice character, but someone with a lifetime of experiences that inform their abilities and who they are. The Lifepath character creation mechanic featured in Cyberpunk 2077 dates back to 1977 and Miller attempting some semblance of Asimovian social realism within a sci-fi setting. Pondsmith’s extreme attention to detail for Internet hacking, or “netrunning,” has also had substantial reach, with dungeon-like charts of enemy mainframes and arsenals of programs that would later inspire the Netrunner card game. This sort of mini-game within a TRPG is in direct dialogue with, say, Miller’s similar attention to starship building: “Traveller was also unique in its day as the first RPG that really gave the game master tools. The rules encourage game masters to get in there and get their mental hands dirty — the tools for making ships, planets, animals, and aliens are all laid out in lucid, precise text, just begging to be used. Need a spaceship? [The game] shows you how to build the ship you want, customized and ready to be improved.”

What we as game designers now know as choice design, randomization tables, and customizability, Miller had framed as a means of giving players “realistic” moves within his brand-new sci-fi universe. Pondsmith’s initial published games from the early 1980s, Imperial Star and Mekton, appear much more obsessed with these particular sub-systems than the act of character embodiment and role-play. Yet Mektonillustrates another quintessential element of Pondsmith’s oeuvre, and that is that stylish (in this case, mecha) design triumphs alongside realism. Attebery and Pearson (2018) note the importance of style and fashion within not only the imagery but also the very mechanics and rules text of Cyberpunk 2020. Here, the surface-level attractiveness of manga such as Mobile Suit Gundam cannot be underrated as an influence. Pondsmith’s realism is the law of the land, until he determines that something would simply look cool, which in that case then it is brought into being on the basis of style over substance.

In summary, I’d like to portray Pondsmith as an innovative transmedia world creator, adept at the “media mix” (Steinberg 2012) required to further promote his games work. It should come as no surprise that he has now risen to prominence with Cyberpunk 2077, albeit accompanied by many other tabletop RPG designers who became videogame superstars: Warren Spector, Greg Costikyan, Richard Garriott. We find the roots of cyberpunk gaming in what Jon Peterson (forthcoming) calls “the two cultures” of sci-fi/fantasy fandom and wargaming, where D&D came from, but ultimately it was the Mobile Suit Gundam manga and Traveller that would spur Pondsmith to create role-playing games, not D&D. His background in child psychology and graphic design had him side with the player in approaching his cyberpunk texts. For many of my generation, Pondsmith’s graphic design, filmographies, biographies, lifepath narrative design, roles, equipment, and continuous worldbuilding in the Cyberpunk 2020 universe over the past 3 decades were the primary entry point into the genre. Moreover, Pondsmith’s experience with the military and the police all helped him conceive of a future in which every Friday night would feature an urban firefight. The United States in the 1980s was a violent place, and he only saw that violence on the rise in the coming decades.

This makes Pondsmith’s recent 2020 press release for R. Talsorian that focuses on his experiences as a Black American in the time of police rioting against protestors in the wake of George Floyd’s extrajudicial murder all the more powerful. He connects his own experiences as a Black American with larger societal issues and his own fictional world: “‘Your’ cops are out of control. They don’t care about who they work for anymore. Like the cops in Cyberpunk, they work for themselves. They have weapons, power and invulnerability that has been granted to them because of the devil’s deal the people in power made with them since the 90’s.” And then he returns to one of the classic modes of science-fiction interpretation: the Cassandra-like caution against dystopia, “If this goes on, then…”

“When I wrote Cyberpunk many years ago,” he recalls, “I meant it as a warning, not an aspiration. Of what happens when Power, Money, and Ruthlessness combine. Of what happens when the America you think you know morphs into a tyrannical state that combines the worst of corporate excess with the worst of authoritarian tendencies. We’re speeding on the way towards that Dark Future right now, and the color of your skin, or the money in your bank account are not going to spare you. It’s time to wake up; to face down the people who want in the end, to enslave all of us.” Cyberpunk 2020 and Cyberpunk 2077 remain influential and indelibly in the discourse precisely because Pondsmith’s viewpoint aligns with his own experiences of violence, greed, tech, privatization, and racism. Can his late-stage work help call us all to action against such a “Dark Future?” One can only hope.

Works Cited

- Appelcline, Shannon (2014). Designers and Dragons: The 80’s. Silver Spring, MD: Evil Hat Productions.

- Attebery, Stina and Pearson, Josh (2018). “‘Today’s Cyborg is Stylish’ The Humanity Cost of Posthuman Fashion in Cyberpunk 2020.” Cyberpunk and Visual Culture. Eds. Graham J. Murphy and Lars Schmeink. New York: Routledge. 55-79.

- Chin, Kazumi (2020). “How not to write RPGs lmao.” Twitter. 7 April https://twitter.com/kazumiochin/status/1247624219669610497?s=20

- Cyberpunk 2077 (2020). Video Game. Warsaw, Poland: CD Projekt Red.

- “Cyberpunk creator talks clown gangs and making the biggest RPG of 2020 | Cyberpunk 2077 Interview.” (2019) Rock Paper Shotgun. YouTube. 28 August https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K2j8cKfGb-M

- Gygax, Gary and Arneson, Dave (1974). Dungeons and Dragons. Lake Geneva, WI: TSR.

- Lavender III, Isiah and Murphy, Graham J. (2020) “Afrofuturism.” The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture. Eds. Anna McFarlane, Graham J. Murphy, and Lars Schmeink. New York: Routledge. 362-372.

- Lowder, James, ed. (2007). Hobby Games: The 100 Best. Seattle, WA: Green Ronin.

- Mobile Suit Gundam (1979-1981). Dir. Yoshiyuki Tomino. Tokyo, Japan: Nippon Sunrise.

- Miller, Marc W. (1977) Traveller. Normal, IL: GDW.

- Peterson, Jon. (forthcoming). The Elusive Shift: How Role-Playing Games Forged Their Identity, in Theory and Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Pondsmith, Mike (2020) “Mike Pondsmith: Cops and Racists.” R. Talsorian Games. Blog. 12 June. https://rtalsoriangames.com/2020/06/12/mike-pondsmith-cops-and-racists/

- –––, et al. (1990) Cyberpunk 2020: The Roleplaying Game of the Dark Future. Berkeley, CA: R. Talsorian Games.

- –––. (1984) Mekton. Berkeley, CA: R. Talsorian Games.

- Purchese, Robert (2017) “Making Cyberpunk: when Mike Pondsmith met CD Projekt Red.” Eurogamer. 13 July https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2017-07-12-making-cyberpunk-when-mike-pondsmith-met-cd-projekt-red

- Steinberg, Marc (2012). Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Discord Discussion

This discussion has been copied from the Discord server, names have been reduced to first name, discussion threads have been grouped and edited for better readability.