Cyberqueer: The Inclusive Design of Cyberpunk Video Games

According to Karen Cadora’s provocative statement, “[r]umor has it that cyberpunk is dead” (1995, 257). However, that does not seem to be a case with video game medium, where cyberpunk has always been and continues to be popular as reflected both in the mainstream industry, where CD Project’s Cyberpunk 2077 is currently one of the most anticipated new titles, and the independent industry, which in the past decade allowed the creation of one of the most innovative and definitely most inclusive games.

Although initially both gamers and game scholars emphasized the difference between the casual and hardcore play practices, the latter became associated with toxic gamer masculinities especially after the harassment campaign arose around the #Gamergate hashtag . The event, which included attacks on feminist journalists, game designers, and game scholars (Massanari 2017), revealed the underlying misogyny and sexism of the gamer culture and the game industry, at the same time emphasizing the need for more inclusive spaces. Without the restrictions of big-budget game companies, the independent game developers more often follow have more freedom to experiment with form and create content that follows postulates of inclusive game design (Chess 2017) and feminist programming strategies (Cassell 1998).

Although perhaps it is surprising that more developers did not choose cyberpunk setting for their games, it is hard to argue about its popularity. From Deus Ex trilogy (Ion Storm and Eidos Montréal 2000-2011), exploring transhumanist themes in the dystopian futuristic setting to the more current narrative games focused on interpersonal relations and personal stories experienced through the eyes of female taxi drivers in Neo Cab (Chance Agency 2019) and Cloudpunk (ION LANDS 2020). Mirroring the feminist initiatives in the late 20th century to reclaim cyberpunk literature which initially was dominated and shaped by white, cisgender, heterosexual authors, in independent games cyberpunk becomes a tool of creating inclusive spaces. In the presentation I concentrate on two games which draw from the classic hard-boiled noir cyberpunk detective stories: 2064: Read Only Memories (MidBoss 2015) and The Red Strings Club (Deconstructeam 2018).

Recognizing the high difficulty, high-stress environments of many mainstream video games, Justine Cassell discussed feminist programming strategies according to which feminist games should “transfer design authority to [the] user,” “value subjective and experiential knowledge,” “allow use by many different kinds of users in different contexts,” “give the user a tool to express her voice and the truth of her existence,” and “encourage collaboration among users.” (Cassell 1998, pp. 304-305). These values are mirrored closely by the discussion of the inclusive design first proposed by Sheri Graner Ray (2004) and, later developed by Shira Chess (2017). They concentrated on such aspects of games as time positivity (games that allow play in short intervals), low risk (small cost for failure), lack of overtly sexualized (female) characters as well as low violence and harassment potential.

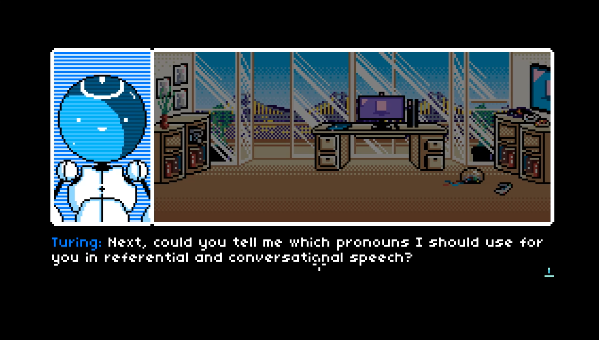

First game which I discuss briefly is 2064: Read Only Memories, a dialogue-driven adventure game prominent for its inclusive use of gender pronouns. The game is set in 2064 Neo-San Francisco, where personal assistant robot (ROMs) replaced smartphones and computers. The game begins when Turing, a prototype of the self-conscious robots, asks the player’s character for help in finding their creator, who has recently been kidnapped. While the main character’s appearance is never showed, it is 2064’s character creation that deserves particular attention. In order to update their database to “be able to assist [the character] more successfully” Turing asks about the character’s (and, with that, player’s) name, dietary restrictions, and preferred pronouns which can be either chosen from the list of five (they/them, she/her, he/him, ze/zir, xe/xir) or provided on one’s own. The inclusion of both the pronoun “they” and the less common pronouns creates a space for self-expression for those players who do not identify with the binary gender options. This is of additional significance due to the fact that with the growing representation of non-heterosexual expressions of desire, non-normative gender identities are still often omitted from the discourses (Shaw and Friesem 2016)

Apart from the character creator, 2064: REM features other non-normative character, the most prominent examples of those who identify as non-binary and whose preferred pronoun is “they” are a human hacker Tomcat and Turing. What needs to be noticed is the sensitivity with which the creators approached both characters who are not expected to explain themselves — Turing explains their feelings toward the human concept of gender only because they consider player character their friend. Although science fiction has been criticized for either overly sexualizing alien and cyborg bodies (coded as feminine), often the non-human “otherness” is equated with being genderless or asexual, which, rather than offering positive representation, further marginalizes and dehumanizes the non-normative genders and sexualities (Sinwell 2014).

The Red Strings Club similarly plays on nostalgia for the classic detective cyberpunk storylines: in the future, in which majority of humans use body modifications, the protagonists investigate the corporation which intends to use these enhancements to control the way their users experience emotions. Emotions are at the core of the game as the eponymous The Red Strings Club is famous for its owner’s ability to make drinks that tune in the customer’s soul, enhancing their underlying emotions. While the gameplay does not follow Cassell’s feminist programming guidelines, it does meet some of the Chess’ criteria of inclusive design, including the lack of risk or time constraints and the diverse characters including Donovan, an owner of the eponymous club and his partner, Brandeis. Furthermore, it could be argued that the inclusivity does not lie predominantly with the representation[1], but with the dialogue-driven gameplay, simple and forgiving mini-games, and the overall aesthetic that draw from nostalgia towards pixel art of old point-and-click adventure games.

The presentation included a (very) short summary of two titles in order to show different ways in which cyberpunk video games attempt to follow the rules of the inclusive design. Different video game creators choose cyberpunk to envision futures where one can express their identities without fear of oppression. The queer utopia coexists there with the political dystopias: as the genre explores the loss of humanity and the invigilation of the government/corporations in the lives of the citizens, reflecting the past and present anxieties, these scenarios are utopian in the sense that they allow the freedom of self-expression. Queer people do not have to fight for validation and recognition and are not marginalized nor oppressed for who they are.

Bibliography:

- Cadora, Karen.. “Feminist Cyberpunk.” Science Fiction Studies vol. 22, no. 3, 1995, pp. 357–372.

- Cassell, Justine. “Storytelling as a Nexus of Change in the Relationship between Gender and Technology: A Feminist Approach to Software Design.” From Barbie to Mortal Combat: Gender and Computer Games, edited by Justine Cassell and Henry Jenkins, MIT Press, 1998, pp. 298–327.

- CD Project. 2020. Cyberpunk 2077. Warsaw: CD Project.

- Chess, Shira. Ready Player Two: Women Gamers and Designed Identity. University of MInnesota Press, 2017.

- Deconstructeam. 2018. The Red Strings Club. Austin: Devolver Digital.

- Lavigne, Carlen. Cyberpunk Women, Feminism and Science Fiction: A Critical Study. McFarland, 2013.

- Massanari, Adrienne. “#Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures.” New Media & Society, vol. 19, no. 3, Mar. 2017, pp. 329–46.

- MidBos. 2015. 2064: Read Only Memories. San Francisco: MidBoss.

- Ray, Sheri Graner. Gender Inclusive Game Design: Expanding The Market. Charles River Media, 2004.

- Shaw, Adrienne. “Where Is the Queerness in Games? Types of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Content in Digital Games,” 10, 2016, pp. 3877–3889.

- Sinwell, Sarah E.S. “Aliens and Asexuality: Media Representation, Queerness, and Asexual Visibility.” Asexualities: Feminist and Queer Perspectives, edited by Karli June Cerankowski and Megan Milks, Routledge, 2014, pp. 162-73.

- Todd, Cherie. “COMMENTARY: GamerGate and Resistance to The.” Women’s Studies Journal 29, no. 1, 2015, pp. 64–67.

- Walker, Austin; Riendeau, Danielle; Zacny, Rob (2018-01-22). “How ‘The Red Strings Club’ Sabotages Its Hopeful Cyberpunk Vision”. Waypoint. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

[1] It has to be noticed that despite the positive representation of non-normative sexualities, one of the characters is revealed to be transgender through the use of the name given at birth (“deadname”), which is considered offensive or even violent (Walker 2018).

Discord Discussion

This discussion has been copied from the Discord server, names have been reduced to first name, discussion threads have been grouped and edited for better readability.