FRIDAY December 4th, 2020 – #CyRN – Schedule below…

Cyberpunk’s indebtedness to music is obvious from the moment that Bruce Sterling acknowledge the Movement’s relation to the “modern pop underground” (xi), and kinship in the “rock video”, “in the jarring street tech of hip-hop, and scratch music; in the synthesizer rock of London and Tokyo” (xi-xii). And cyberpunk has picked up this relation, shown us rockers and rappers—from Cadigan’s synthesizing rock in Synners to the Wachowski’s tribal techno party in Matrix: Reloaded. But that is literary or cinematic representation of music—what about the other way around? What influences did cyberpunk have on the development of music, pop or otherwise?

Karen Collins argues that industrial and cyberpunk share the same “tradition of twentieth-century Western dystopias” (167) and analyses their similarities in theme, ideology, imagery and style. And Roy Christopher argues for a relation between cyberpunk and hip-hop in his book Dead Precedents. Similar arguments can be made for synthesizer music, electro and techno, but also for metal and prog rock. Not to forget that cyberpunk films have had radical and interesting soundtracks to provide their imagery with a sonic relation.

Presentations are now online to watch/read!

Click on the Links below…

§1: Nicholas Laudadio – “Cyberpunk Music”

This chapter (from The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture, available to CyRN members on Discord) examines the development of cyberpunk as a musical endeavor, from its origins in the early days of electronic music and the work of artists like Kraftwerk, David Bowie, and Gary Numan through its full realization as a mode in the 1980s and 1990s with industrial electronic outfits like Front 242, Front Line Assembly, Clock DVA, The Cassandra Complex, and KMFDM. The chapter also takes into account other musical styles that traffic in cyberpunk themes, including metal bands Voivod and Fear Factory and hip hop artists Deltron 2020, Dr Octagon, El-P, and Cannibal Ox. The chapter concludes with an examination of cyberpunk’s cinematic soundscapes, including composers like Vangelis, Wendy Carlos, and the collective Geinoh Yamashirogumi, leading into a broad consideration of cyberpunk’s contemporary legacy as a force for cultural and musical inspiration.

§2: Joseph Hurtgen – “Records that Warp: Electronic Music and Cyberpunk”

Electronic music is an important expression of cyberpunk culture. The rise of samplers, drum machines, and synthesizers paired with bass guitars and electric guitars allowed for a new type of music that remixed older musical forms into a repetitive, often industrial and robotic sound that accompanied our progression into the digital age. The earliest expressions of electronic music were synth heavy–like Kraftwerk and Brian Eno–and originated in the ‘70s. Video games, using MIDI–musical instrument digital interface, contributed to the prevalence of electronic music. Remixing was an important aspect of electronic music. Often, artists sampled breakbeats from jazz and funk records of previous decades and sped up the BPMs to create a distinctively futuristic sound. In the early ‘80s, African Americans in Detroit created techno with drum machines and samplers as a way to express visions of an egalitarian future. Consider Cybotron’s “Cosmic Cars,”–”I wish I could escape from this crazy place.” The song is about flying off into space in one’s own car-like spaceship and the subtext is that technology will give mobility and agency to disenfranchised people. This new genre shares its nascence with cyberpunk, a literary movement that had similar aims–consider the hacker’s ability to democratize information, to restore a balance of power between society’s most powerful institutions and the common man; has echoes of the new digital age with entry into cyberspace, a world of digital memory, and the alteration of identity and psychology via technological experiences and digital disruptions, including data corruption and erasure; and is similarly a remixed genre–Gibson’s seminal cyberpunk work Neuromancer is a mash-up of Chandlerian detective noir, the philosophy of postmodern philosophers like Paul Virilio and Jean Baudrillard, and the New Wave and other SF of the ‘70s like John Brunner, Philip K. Dick, and K.W. Jeter.

§3: Jim Osman – “Neo-Opera, 21st Century Post-Veristic Opera as Cyberpunk Provocation”

This paper presents a case for the future of opera lying in the Cyberpunk space. It will look at how the art form can be developed in the 21st century in line with Wagner’s theory of the Gesamtkunstwerk (the total work of art) through an increased use of technology.

This paper argues that if Cyberpunk can be characterised as High-tech and Low-life then opera, particularly the late 19th century trend of Italian verismo opera (directly influenced by the verismo literary tradition, including writers such as Émile Zola ) can be characterised as high-art and low-life. Both opera and Cyberpunk require a whole-hearted acceptance of an alternative reality and not only does Cyberpunk offer a ripe setting for operas, but the increased use of technology offers the director the opportunity to get closer to Wagner’s notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk. If we combine High art with Hi-tech and retain the low-life/verismo of classical opera/cyberpunk, then Neo-opera, a cyberpunk operatic provocation, might be the future of the art form.

I will case-study Valis by Tod Machover, ROBE by Alastair White and I Screwed up the Future by Jason Cady as examples of contemporary operas that explore cyberpunk themes.

§4: Andrew Wenaus – “The Engineer and Architect of Cyberpunk Cut-up Music: Iannis Xenakis’ Granular Synthesis”

Behind each cyber cowboy jacking into cyberspace, is the mad technician: the rogue scientifically-minded, engineering-competent, coding mastermind making the cyber world possible. While cyberpunk literature owes much of its frenetic energy and accelerated fragmentation to punk, hip-hop, MTV, and techno remix, this cut-up ethos found inspiration in William S. Burroughs, who owes much to Brion Gysin, who owes much to Tristan Tzara, who owes much to a pair of scissors and a newspaper. In this lineage, protest and the avant-garde emerge from shared origins. However, while cyberpunk literature’s influence on music tends to focus on the punk element of guitars, basses, drums, and screams of punk rock, the cyber aspect conjures turntables, samplers, synthesizers, tracking, and computers of hip hop and techno. What I would like to examine here, however, is a trajectory that made the latter “cyber” element possible in the first place: the emergence of an analogue to the “cut-up” in the history of electronic music before warehouse parties, boom boxes, and raves. Beginning with a brief overview of the Futurist and Dadaist tradition,[1] this short talk will focus on the stochastic music of Iannis Xenakis, the Greek engineer, architect, and composer who developed the electronic music equivalent to the cut-up in the 1950s: granular synthesis. This process creates automated cut-ups of recorded audio whereby a tape recording is split into tiny clips (called grains) and reassembled in a complex indeterminate algorithmic pattern based on mathematics. While originally an analogue procedure, this process would later be used in Xenakis’ hypercomplex computer music. Just as the Dadaists captured the process of random reassembling as an act of political resistance, the digital era of the 1980s onward demands engagement with the formative media and agential acknowledgement with the interfaces that govern the narratives of modern life. Xenakis’ granular synthesis aims to continue this resistance in the computer-era but, like the Dadaists, eschews postmodern pop in favour of a kind of supermodernist transcendence. The unpredictable rogue individualism of the Dadaists, beatniks, and punks, however, can today be easily modelled by Silicon Valley: today, the cyber cowboy would simply be a precisely modelled target market. Xenakis’ approach to a musical cut-up technique, however, aims to resist this by engaging with a kind of music that creates a state of mind akin to stochastic agency, rather than individualism. Xenakis’ hyper-complex “stochastic music” is named after “the branch of mathematics that studies the random or irregular activity of particles.”[2] For Xenakis, the effects of merging technology and music have a rather cyberpunk endgame: music “must aim through fixations which are landmarks to draw towards a total exaltation in which the individual mingles, losing his consciousness in a truth immediate, rare, enormous, and perfect”;[3] that is, of technological transcendence and a recalibration of the nervous system as resistance to the neurototalitarian steering of techno-capitalism. Ultimately, I will briefly suggest that Xenakis’ use of technology in music for transcendence and resistance can act as a reminder of the avant-garde lineage that informs so much cyberpunk culture though is often sidelined due to its incompatibility with the commodification practices that pressure much genre art into easily recognizable and consumable tropes. Rather than focusing on the cyber cowboy, then, I will consider the engineer and architect who helped create the bizarre, challenging sonic infrastructures for political and artistic alternatives.

[1] Luigi Russolo, Edgard Varèse, Pierre Schaeffer, John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Kathy Berberian, and Luciano Berio.

[2] Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), 395.

[3] Iannis Xenakis, Formalized Music: Thought and Math in Composition, Revised Ed, (Stuyvesant, NY : Pendragon Press, 1992), 1.

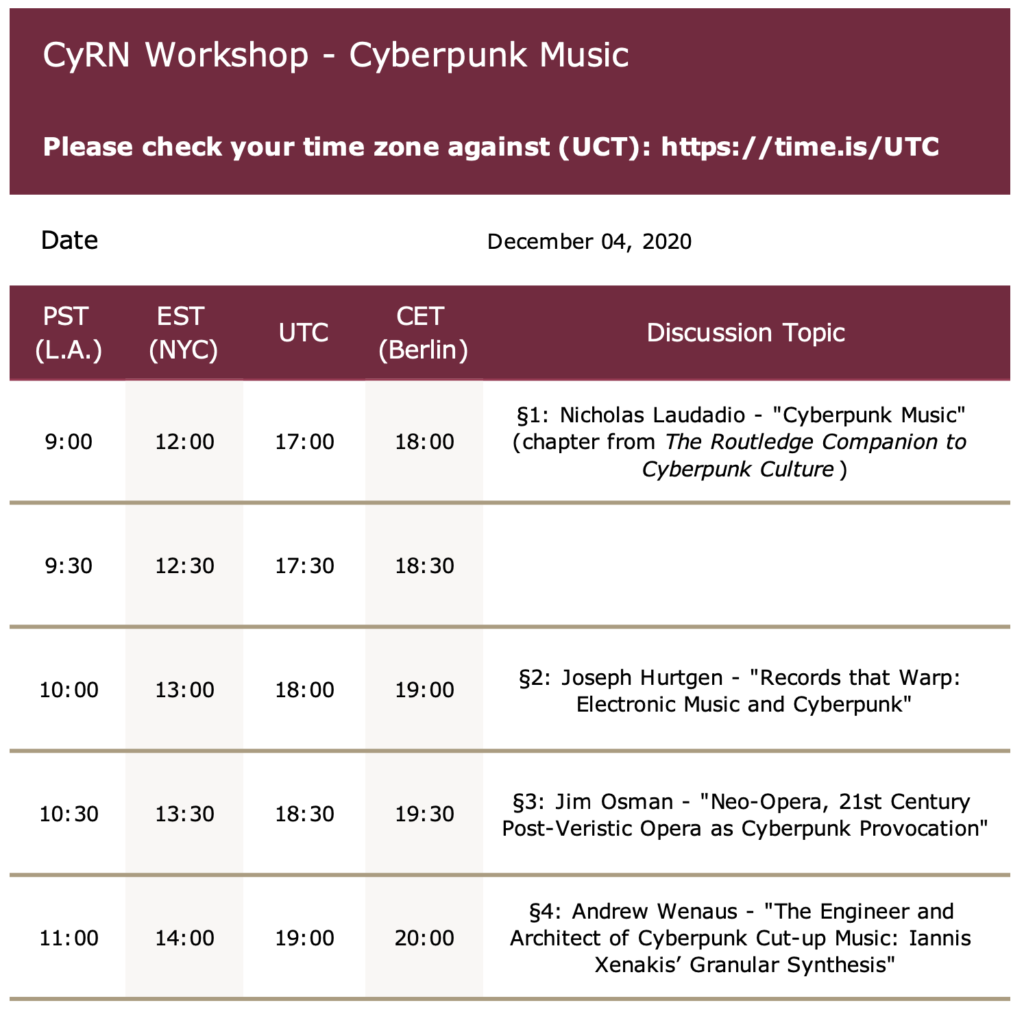

DISCUSSIONS ON FRIDAY – SCHEDULE